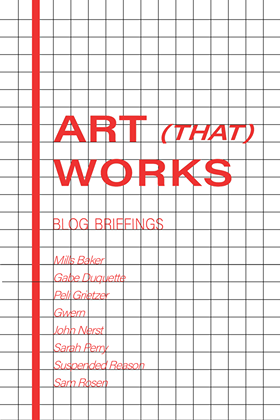

| Title | Art (That) Works |

| Author | Various |

| Tags | art crit, Chris Alexander, Jeurgen Schmidhuber, food metaphors of art, theory |

| Release | Fall '20 |

Ordering instructions: Venmo $10 and the following info to ooo@notnothing.ooo

| TITLE NAME |

| Full name |

| Street/Apt |

| City |

| Zip/Country |

There are two commonplace “pictures” of what art is that we use to justify the pursuit of art. One picture says that great art describes the human condition, or expresses our innermost experiences, or connects us to our unattended thoughts and feelings, or allows us to reflect on our life and memories and circumstances, or to empathize with others or to commune with the cosmos or to understand material conditions of life or whatever. Apart from being kind of old and uncool, this picture’s inconsistent with how crucial “gaming” the cultural moment is for making good art. Or, at least, it’s inconsistent with how crucial gaming the cultural moment is for making good art in spheres like pop music, visual art, film, and avant-garde literature—there are also spheres like literary fiction, or lyric poetry, or off-Broadway theater, where gaming isn’t as important and the “express human condition” picture sort of holds, but weirdly these spheres seem less deep, not more deep, than the spheres where gaming is the life-blood of good art. This is where the second commonplace picture of what art is comes in: the second picture says that there’s a thing called “culture,” which is a sort of social structure that’s formed out of the interaction of everyone’s world-views and desires and beliefs and in turn structures the evolution of everyone’s world-views and desires and beliefs, and making art is a way of intervening in that structure. So on this picture art is a form of politics, in the sense that making art is making a historical intervention in a collective structure (“culture”). On this picture, it makes perfect sense that whether art is good or not depends on how it games its cultural moment—the meaning of the work of art is the dent it makes in culture. But this picture’s not consistent with the fact that most of the really crucial gaming happens at the level of choosing what reverb to use or one-upping every other rapper by making a rap track with no drum loop: aesthetic gaming might be a historical intervention in culture, but it mostly intervenes in the art part of culture, so if we don’t have anything to say about what the significance of art is other than as “intervention” we get weird closed-circuit masturbation. (In the visual art world and the avant-garde literature world people deal with the short circuit of the second picture by proposing that aesthetic form has sympathy, in almost the alchemical sense,with the most abstract, long-term aspects of politics, so keeping your shit aesthetically restless is crucial for the longterm possibility of utopian political projects. I respect this but don’t buy it enough to, like, base my life on it.) When I said at lunch that the way cultural elites treat art became more “zoomed out” I meant that years ago the first picture dominated how overeducated young people talk about art and nowadays the second picture dominates. I think the second picture gets something deeply right—the artworks I admire the most put their gaming front and center—but gets muddled by the instinct to equate “gaming” + “meaningful” with “political,” like in order to explain how something can be both gaming and not-just-a-trend we have to say “by being politics” cause trends and politics are the only two kinds of intrinsically gaming things we can name. Shockingly, the true picture is revealed to be a synthesis of the two imperfect pictures. Basically I think that gaming in art is a lot more like mathematical progress than like political progress.

—Peli Grietzer